|

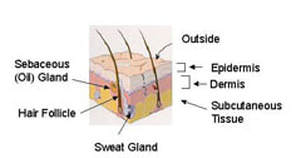

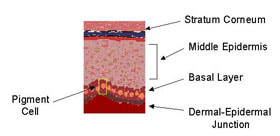

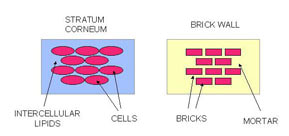

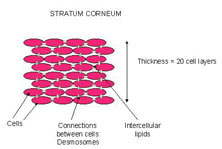

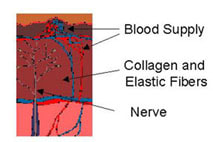

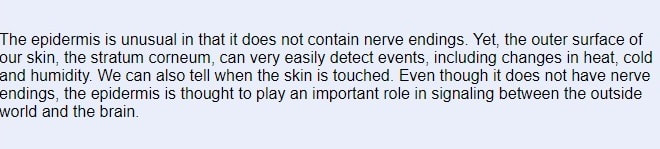

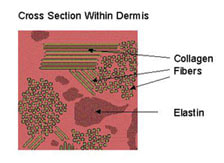

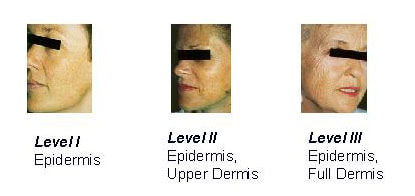

Introduction The skin is a fascinating organ, unmatched in its complexity, yet necessary for all aspects of daily life. Much of the time, the skin functions so well that we only notice it when we are uncomfortable. The skin is our interface or boundary between us and the environment and us and other people. We are always looking for new and better products, practices and solutions to the stress which everyday life places on our skin. This topic covers: - How the Skin Functions - Aging and Its Effects on the Skin - How to Care for and Protect Your Skin - Strategies for Achieving Skin Health How the Skin Functions The skin is the largest single organ of the body, critical for survival, and covers an average area of 21 square feet (think of the floor area of a closet that is 4 feet deep by 5 feet wide). It is the largest organ of immunity from disease and protects by: - Keeping water and essential nutrients inside and unwanted, toxic substances outside - Regulating the temperature for warming and cooling - Repairing damage from cuts, burns, environmental insults, or other trauma The skin differs from organs like the heart or lungs because it constantly mends itself by replacing the outer layer daily. It is continually ready to respond to harm. Cuts close over, producing new, pink skin. Sunburned skin becomes dry and peels, giving way to a pink, soft, smooth, and supple replacement layer. The environmental insults signal through the surface to layers below which, in turn, begin the restoration process. The skin's outer layer is a "biological space suit" for life on earth, much like space suits protecting astronauts from the hazardous conditions in outer space. These environmental insults include: - Sun exposure - Climatic changes: heat, cold, high or low humidity (moisture level in the air) - Physical abuse: frictional forces in chafing, rubbing, weight bearing, and shaving hair from the skin - Products like soaps, dish washing detergents, household cleaning products, paint, grease, solvents, rubbing alcohol, and cosmetics - Skin-tight clothing - Water in some situations: extended exposure to water has been shown to damage the skin - Lifestyle or habits: smoking, drinking alcohol, lack of sleep These insults, including sun exposure, can suppress the immune system which can result in skin cancer. Protection of the skin from these insults is, therefore, critical for good health.  Skin Structure An understanding of the skin structure and function is essential for the health care consumer to provide the proper care for his/her skin. The skin has three major layers: - Epidermis - Dermis - Subcutaneous tissue Each layer has unique functions. This diagram shows a cross section: The epidermis is the outermost layer and it directly interacts with the environment. The epidermis protects by providing a barrier to outside materials (products, water, etc.) and by filtering sunlight. The epidermis is self-renewing. It replaces itself continually, unlike any other organ of the body. The dermis is beneath the epidermis. It contains the major structure-providing tissue fibers, collagen and elastic. It also contains the vascular system to provide a blood supply and nerve cells to process information to and from the brain. The subcutaneous tissue contains the fat pad and muscle.  The Epidermis Like all tissues, the epidermis is made up of cells which have specific functions in the skin. A cell called the keratinocyte makes up most of the epidermis. The functions of the stratum corneum, the middle epidermis, the basal layer, and the dermal-epidermal junction are highlighted. The Stratum Corneum The stratum corneum is the outermost layer, directly in contact with the environment. It is about half the thickness of a piece of notebook paper. On average, the stratum corneum is about 20 cell layers thick. Despite its thin dimensions, the stratum corneum is incredibly strong. The cells are in a very well organized pattern.  The stratum corneum is the outermost layer, directly in contact with the environment. It is about half the thickness of a piece of notebook paper. On average, the stratum corneum is about 20 cell layers thick. Despite its thin dimensions, the stratum corneum is incredibly strong. The cells are in a very well organized pattern. The stratum corneum has been described as a "brick and mortar" structure, as shown here: The cells are the bricks and the lipids are the mortar. Lipids are "oily" materials that do not easily mix with water, such as cooking oil, petroleum jelly, baby oil, and grease. The skin lipids are mixtures of materials that form a very well organized structure between the cells. The lipid layer helps keep water in the stratum corneum by limiting passage of water from beneath. The lipids also keep water and water loving substances out of the body. The stratum corneum contains water that is associated with the protein materials in the cells. The cells hold onto water to keep them flexible and to allow the body's movement without cracking the upper layer.  Neighboring stratum corneum cells are joined together through small attachments, called desmosomes. In a sense, these are like small "rivets". Each cell is attached at many points to nearby cells (cells above, beneath, adjacent). These multiple attachments provide considerable strength to this tissue. The very top layer of the stratum corneum normally comes off or "sheds", about one cell layer per day. You can observe this layer by placing a piece of clear tape and put it on the back of your hand for a few minutes. Remove the tape and notice the flaky material, which is the top layer of cells. The desmosomes need to break in order to free the cells. This process, called desquamation, is carefully programmed to occur at the proper time. The Middle Epidermis Right below the bottom of the stratum corneum lies the middle epidermis. At the top, the cells are flatter than the rest of the layer. These top cells contain lipids and release them as they move upward. These lipids then become the stratum corneum lipids. The remaining cells are keratinocytes which have a cube shape and contain bundles of filaments that help protect the skin from the friction during movement and rubbing. Over time, the cells move upward to the top of the middle epidermis and eventually become stratum corneum cells. Their features change over time during this renewal and replacement process. The Basal Layer The basal layer rests at the bottom of the middle epidermis. The basal cells are different, however, because they actively divide to create new basal cells. The older cells move up to form the middle epidermis. All cells of the epidermis begin at this point by the process of cell division. The cell division process needs protein and other nourishment that are supplied by the functions of the dermis. The basal layer contains a unique type of cell called the melanocyte or pigment cell. Unlike other basal cells, the melanocyte does not move upward. The melanocyte's job is to make a substance called pigment, or melanin, which contributes to the coloration of the skin. Melanocytes go into action to make melanin when ultraviolet radiation interacts with the skin. The melanin is transferred from the melanocyte to the keratinocytes of the middle epidermis, to protect the nuclei of these cells from being damaged by radiation. Dark spots on the skin, such as freckles, are clusters of epidermal keratinocytes with melanin concentrated in them. Sun tanned skin has a more uniform distribution of keratinocytes with melanin. Both conditions are the response of the skin to sun exposure. As the name suggests, the dermal-epidermal junction is right between the epidermis and the dermis. This layer of the skin holds the epidermis onto the dermis. It provides support to the entire tissue to help hold it in place. Epidermal Cell Summary The epidermis performs a wide variety of functions. Epidermal cells, or keratinocytes, move from the basal cell layer to the top of the stratum corneum in about 28 days. The specific time depends on the location on the body, the overall state of health, and the type and severity of environmental insult. The outermost layer of the stratum corneum comes off each day. When injury to the skin occurs, again from some sort of damage, the whole replenishment process works overtime to restore the skin to its proper condition and to ensure a protective barrier. In the case of serious injury, such as a major burn, the healing process requires a long time. The melanocytes, or pigment cells, housed in the bottom of the epidermis, produce melanin to protect the epidermal cells from ultraviolet damage. The epidermis is unusual in that it does not contain nerve endings. Yet, the outer surface of our skin, the stratum corneum, can very easily detect events, including changes in heat, cold and humidity. We can also tell when the skin is touched. Even though it does not have nerve endings, the epidermis is thought to play an important role in signaling between the outside  The Dermis The dermis is below the epidermis and above the subcutaneous tissue. The epidermis is unusual in that it does not contain nerve endings. Yet, the outer surface of our skin, the stratum corneum, can very easily detect events, including changes in heat, cold and humidity. We can also tell when the skin is touched. Even though it does not have nerve endings, the epidermis is thought to play an important role in signaling between the outside world and the brain. Collagen and elastin fibers make up a large part of the dermis. The thick fibers of collagen support the skin. Elastin fibers are very flexible and impart mechanical strength and resiliency to the skin by allowing it to stretch. When the elastin is in good condition, the skin returns to its original shape readily when it is flexed or stretched. If the elastin and collagen are in poor condition, the skin lacks resiliency, sags, and develops noticeable wrinkles. The major functions of the dermis are to support the epidermis, to provide bulk and to anchor the skin. Importantly, the dermis contains blood vessels that bring oxygen and other nutrients to the basal layer for the cell division process. Nerve endings are also found in the dermis. Presumably they take signals from the epidermis, including the stratum corneum, and transmit them to the brain. This signaling function is unique because there are no nerve cells in the epidermis. The major parts are shown here: The diagram shows that the dermis has a compact array of fibrous material, the collagen and elastin, necessary for support, resistance to damage, and overall health. Aging and Its Effects on the Skin The effects of aging on the skin are currently of great interest. People are living longer and more active lives than ever before. The "baby boomers" are now in their 30s, 40s and 50s. They have large disposable incomes and no intention of looking old. For them, "looking good" and "feeling good" go hand in hand. The process of skin aging process has two parts: natural aging, due to increasing chronological age, and solar aging, due to the effects of the sun. Natural Aging Natural aging includes all of the environmental and genetic factors that impact the skin, other than those due to solar damage. As the skin ages, the cell movement from the bottom of the epidermis (basal layer) to the top (outermost stratum corneum) becomes slower. The skin surface becomes rougher, with a more uneven texture, because the cells are shed more slowly. Often the slowed desquamation process (remember the tape on your hand experiment?) results in the formation of large clumps of cells, observed as scales or dry skin flakes. The uneven texture and scaling tend to make your skin look duller. The epidermis becomes thinner and the skin becomes more fragile. In the dermis, the elastic fibers become coarse and then disappear. The coarseness makes them less elastic. The skin returns to its original state much more slowly when it is stretched. The blood vessels decrease in size and number. This change influences the nutrient supply to the basal layer and accounts in part for the slower rate of epidermal replenishment. Some of the factors in natural aging are determined by the genetic make up of the individual. Much more needs to be learned about specific genetic influences. Photoaging & Sun Damage Sunlight causes significant damage to the skin which, unfortunately, does not show up right away. In fact, many people believe sun or tanning bed exposure equals a healthy appearance and healthy skin. This "socially desirable appearance" comes at the expense of poor appearance and poor skin health as one gets older. Tanning beds provide ultraviolet radiation through special bulbs and damage the skin as much as the sun itself. Individuals who spend most of their time indoors are still exposed to damaging rays when they do go outside. Sun damage takes two forms, photoaging and skin cancer. The majority of a lifetime sun exposure occurs before the age of 20. Children receive three times more exposure to the sun than adults. The damage process starts early in life unless the skin is protected. Many non-melanoma skin cancers could be prevented with proper protection from the sun. Photoaging: The Epidermis Ultraviolet radiation from the sun penetrates the stratum corneum. It affects the epidermal cells and causes a change in thickness. Some areas of the epidermis increase in size and others decrease to produce an irregular, non-uniform structure. The normal, orderly processes of the epidermis are disrupted. As a result, the epidermis cannot produce a proper stratum corneum. The "defective" stratum corneum is irregular and the very top layer does not slough off properly. Consequently, the skin surface texture becomes rough and irregular. The skin pigmentation, or coloration, becomes blotchy and irregular. This happens because the melanocytes are forced, by the ultraviolet radiation of the sun, to produce pigmentation. The pigment is transferred to the keratinocytes of the middle epidermis and these spots become visible when we view the skin surface. In addition, the skin tone becomes sallow and appears to lack the vitality of a healthy state. Photoaging: The Dermis Sunlight breaks down the collagen and elastin fibers in the dermis. These structures become irregular. This irregularity in the dermal support tissue leads to visible wrinkles. The fibers also lose their elasticity, causing the skin to sag. Sun damage leads to chronic inflammation of the dermis. As a consequence, the epidermis does not function properly. The chronic inflammation causes the epidermis to become thicker as it attempts to repair the damage. Levels of Photoaging Photoaging occurs to varying levels. In Level I, ultraviolet radiation causes changes in the epidermis only. The alterations result in a dull, rough outer layer and in pigmented spots. In Level II, changes are caused in both the epidermis and the upper part of the dermis. Injury from the sun leads to increased wrinkling, and alterations in pigmentation and texture that are greater than those in Level I. Consequently, the skin's features are not uniform, thereby exaggerating the effects. In Level III, changes occur in the epidermis and throughout the dermis. The wrinkling is more pronounced and the skin texture is much less uniform, often pebbly in appearance. The skin takes on a leathery appearance. How to Care for and Protect Your Skin Skin care begins with a healthy lifestyle. Strive to do the following, wherever possible: drink plenty of water, eat a balanced diet with sufficient vitamins, exercise regularly, get enough sleep, avoid smoking and the use of tanning beds, minimize alcohol consumption, and manage daily stress. Some of these lifestyle techniques are easier to sustain than others, but they represent useful goals. Care for your skin in each of the following areas. Skin Cleansing For daily hygiene, use a mild cleanser. Remove facial make up completely. Use lukewarm water for all cleansing. Rinse the skin thoroughly to remove cleansing materials from the skin surface. Gently pat dry and avoid rubbing. Skin Moisturizing In "moisturizing," water is added to the skin. Moisturized skin is more flexible than dry skin. Application of moisturizer immediately after washing helps keep water within the skin. Skin moisturizers: 1 improve hydration (moisture content) 2 add a "protective" layer on the skin surface to help hold moisture within the top layers. A large number of emollient creams and lotions are available. The protective layer provides a barrier to water loss. Therefore, water remains in the upper layers of the epidermis and makes the stratum corneum more flexible. Read product labels to check for certain ingredients. One of the most common ingredients for increasing hydration is glycerin, which holds onto water within the outer layers following application. A second type of ingredient serves as a barrier when applied to the skin. These materials include petrolatum, mineral oil, and certain plant oils. They are lipid in nature and protect the skin by minimizing water loss from the epidermis and by providing a barrier to intrusion. A second group of skin care materials is alpha hydroxy acids, known as the fruit acids (glycolic acid, lactic acid, etc.), and beta hydroxy acids (salicylic acid). These materials create a smoother skin surface by hydrating the surface layers and weakening and breaking the attachments between the stratum corneum cells. This process, known as exfoliation, assists in the removal of surface dry, scaly patches. Cancer Awareness We advise periodic evaluations of any marks, moles, or pigmented areas by a trained health care professional. Any mole that changes in size or has an irregular border must be checked. Prevention of skin cancer involves avoiding sun damage and detecting trouble spots early. Be aware of changes in your skin and have them evaluated. Adult Skin Care An individual's skin care regimen should include basic elements, as well as those tailored to specific needs and lifestyles. For the early adult (20-35 years), we recommend cleansing with a non-soap product and rinsing well and moisturizing, particularly in cold weather. Application of sun screens and sun blocks on a daily basis at an SPF value of 15 is essential. For early signs of damage, such as uneven pigmentation or fine wrinkles, a retinoid product should be considered. Control of acne is often an important element. For the middle adult years (35-65), cleansing, moisturizing, sun protection, and use of retinoids are recommended. Acne can be problematic for this group, as well as early adults and teenagers. For persistent acne, various medications and treatments are available. Individuals may consider restorative techniques, such as the chemical peel, dermabrasion, or laser resurfacing, to correct the damage caused by sun exposure. For the older adult (over 65 years), the cleansing, moisturizing, and sun protection routines should be followed. Restorative techniques can provide noticeable improvement in skin damaged by sun exposure. Regardless of age, sun exposure should be minimized and sun screens and sun blocks applied routinely. They will prevent additional damage. Infant Skin Care At birth, the full-term human newborn is well-suited for life in a dry environment. The infant's skin provides an efficient and protective barrier during the transition from the water environment to life outside. The full-term infant's skin functions very well. The stratum corneum barrier protects against water loss and infection. The effective functioning of this barrier is surprising, particularly because the infant has spent nine months in a very wet environment. Nature has provided mechanisms to protect the infant's skin in utero and to allow the stratum corneum to develop properly. For infants born prematurely, the skin barrier is immature. The more premature the infant is, the poorer the skin barrier. Poor barrier function results in high evaporative water loss, which has negative consequences for temperature control and metabolism. Infants born less than 30 weeks gestation have a significantly poorer stratum corneum barrier than those born at term and at 32-34 weeks gestation. Once the baby is born and exposed to dry conditions, the barrier forms rapidly. This maturation takes place within the first five days of life for the preterm infant of less than 27 weeks. Bathing For routine bathing of the infant's skin, we suggest a liquid product. Several brands are commercially available. The product should be diluted with water before it is applied. The infant should be rinsed thoroughly with water to minimize any cleanser residue left on the skin that may disrupt barrier function. Diaper Area Care Diaper rash is a common occurrence among infants and young children. Most of the time, the rash is relatively minor and appears as reddened areas within the diaper region. For mild irritation, we suggest cleansing the skin with warm water and a soft cloth. The skin should be dried thoroughly before diapering the baby. A hair drier on a very low setting is effective for drying the skin. At other times, particularly if the infant has been taking antibiotics and experiences diarrhea, the rash can be more severe. The area should be cleansed with warm water and a soft cloth. Apply a diaper rash product to the affected areas. This will provide a "protective" barrier between the skin and the next soiling. Use a product that is easy to cleanse away and do not rub the skin. Ideally, only remove the soiled material. Leave the remaining cream in place to avoid scrubbing the skin. Reapply the rash cream as needed. If the rash does not clear up or if it gets worse, seek medical attention. Sources and References:

Marks, James G; Miller, Jeffery (2006). Lookingbill and Marks' Principles of Dermatology. (4th ed.). Proksch, E; Brandner, JM; Jensen, JM (2008). "The skin: an indispensable barrier". Experimental Dermatology. 17 (12): 1063–72. Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1893). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. Jablonski, N.G. (2006). Skin: a Natural History. Berkeley: University of California Press. Shapiro SS, Saliou C (2001). "Role of vitamins in skin care". Nutrition. 17 (10): 839–844. McGrath, J.A.; Eady, R.A.; Pope, F.M. (2004). Rook's Textbook of Dermatology (7th ed.). Martin, P. Wound Healing-aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science (1997), 276, 75-81. Websites: The Aging Skin The Human Skin Skin Information and Facts

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDrs. Christiaan Janssens Archive

Augustus 2019

Categories |

RSS-feed

RSS-feed